With a chapter never quoted in the NT, we see how Jesus fulfilled what God promised through the Prophets.

The hope Jesus proclaimed was deeply rooted in the promises of the prophets. Matthew keeps telling us that Jesus fulfilled the prophets, using phrases from Zechariah far more than we do today.

Many of us struggle to make sense of how the NT writers used the prophets. Read Zechariah in context, and it may not sound like predictions. For example, the blood of the covenant in Zechariah 9:11 seems to refer back to the Sinai covenant (Exodus 24:8), yet Jesus used the phrase for his Last Supper (Matthew 26:28).

Maybe our understanding of “context” is too narrow. You probably know to check a few verses either side of a quotation, so as not to take it out of context. In a limited sense, that’s true. But for Jesus and the New Testament writers, context was much broader — their place in the story of God.

When Jesus announced the good news of the kingdom, his context was the Jewish world that had not been a kingdom since the exile. Most of them lived in other countries, scattered like sheep without a shepherd. That’s how Zechariah had described them 500 years earlier (Zechariah 10:2; 13:7 etc), and it still described their context in Jesus’ day (Matthew 9:36; 10:6; 15:24).

Jesus fulfilled the prophets not merely by doing some particular thing they predicted. That happened, but it was far more: everything God promised to restore was finally fulfilled in his Anointed. That’s the scope of what Jesus fulfilled: All the promises of God find their Yes in him (2 Corinthians 1:20).

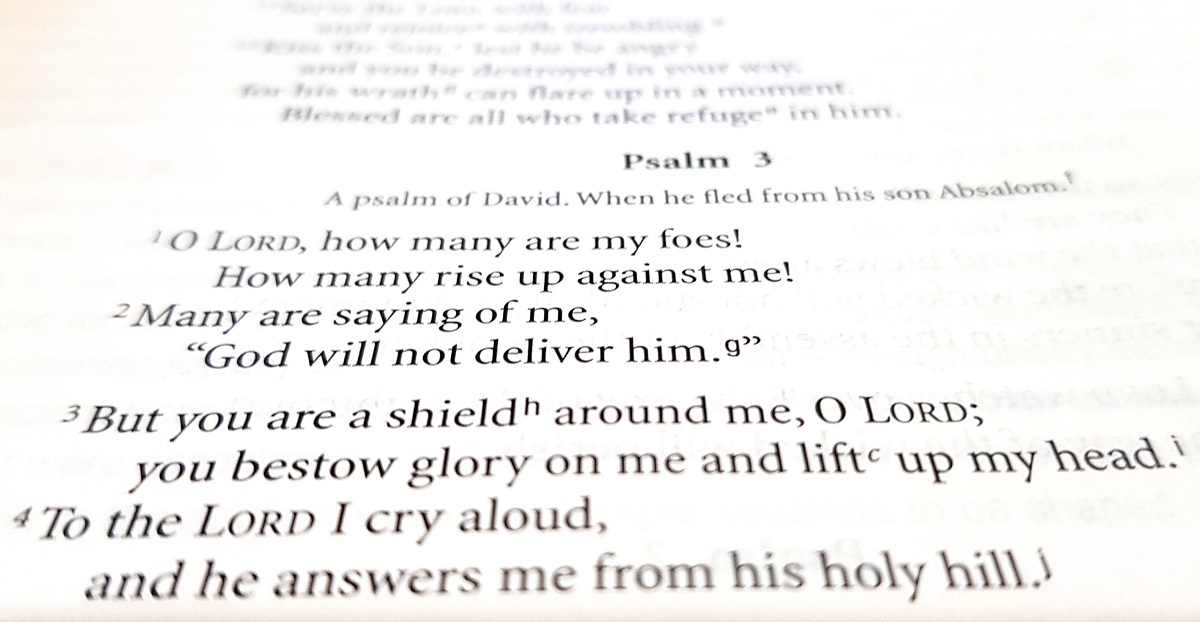

So, let’s take a chapter the NT writers never quoted. How is Zechariah 8 fulfilled in Christ?

Continue reading “How Jesus fulfils the prophets (Zechariah 8)”