As king, Jesus could lay down the law for his people. What he does is to lay down his life for his people.

Open Matthew 5:17-20.

“Don’t think I’ve come to abolish the Law or the Prophets,” Jesus said (5:17). Why did he need to say that? Who would have heard his message as doing away with God’s commands? Why would the crowd on the hillside have had such a thought?

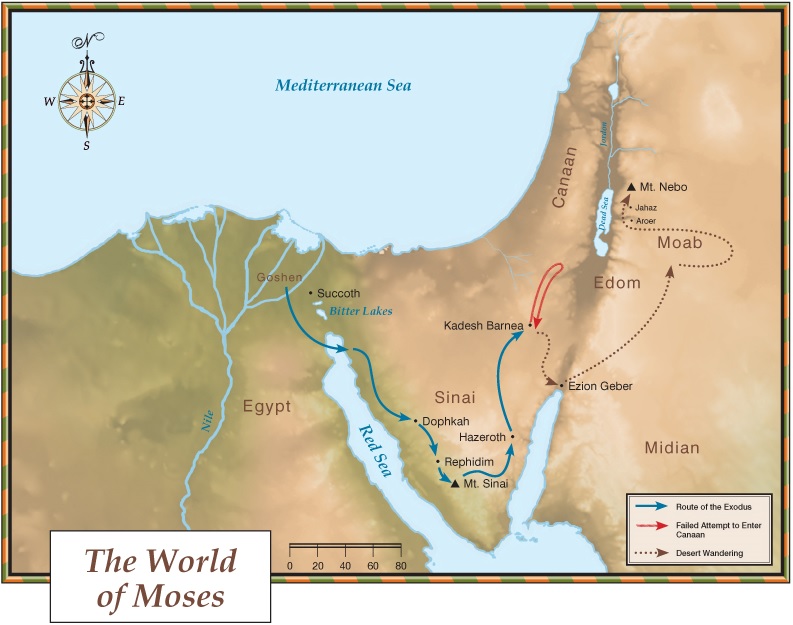

They’d never heard anything like Jesus’ kingdom announcement. Good news: heaven’s reign is being restored to earth (4:17-25). Joy to all the people who would benefit under his reign (5:3-12)! With God’s presence among them, they were as flavour-intense as salt, so brilliantly endowed with the glory of their sovereign that they couldn’t hide (5:13-16).

That’s not how Jesus’ contemporaries taught. The Pharisees expounded Torah commands, calling people to be more obedient. Over the centuries, Jewish rabbis have identified a total of 613 mitzvot (commandments). For each command, they have defined who should obey (males? females? children? foreigners?), how often (constantly? weekly? yearly? once-off), and where (e.g. the festivals are in Jerusalem). They analysed how commands about sacrifices could be obeyed after the temple had been destroyed. Their intense focus on commands is perfectly logical if you believe that God would only restore his kingdom once his people were more obedient.

But that was not Jesus’ message. His approach was so free and joyful that he needed to explain himself to those who thought he should have been calling for obedience. By announcing the blessing of YHWH’s restored reign after six centuries under foreign rule, was Jesus saying that Torah obedience didn’t matter after all? Was he saying that God had changed his mind about disciplining Israel for their disobedience, that Torah obedience didn’t matter and God would give them the kingdom anyway?

Jesus’ answer to that question is categorical:

Matthew 5:18 (ESV)

Truly, I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the Law until all is accomplished.

God was Israel’s political sovereign as much as he was their religious deity. They were called to be a kingdom under God’s kingship. The Torah was their national law. If Jesus was Israel’s king, the son of David who represented the heavenly king on earth, he would undermine his own authority if he taught people to ignore their heavenly sovereign’s laws. He would not their great king, but the person of least significance in the whole kingdom:

Matthew 5:19 (ESV)

Therefore whoever relaxes one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do the same will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever does them and teaches them will be called great in the kingdom of heaven.

His opponents relax. Jesus is, after all, calling people to obey Torah. Then, just as they let down their guard, Jesus throws the final punch: “These Pharisees and Torah interpreters who constantly point out how you don’t measure up? You’ll all have to do better than that mob or Israel will never have God’s reign!” (5:20 paraphrased. Note: you in this verse is plural).

Jesus was using irony to make a serious point. Why was he so antagonistic to the Pharisees and Torah teachers? Matthew provides further detail as his Gospel account unfolds, but one reason was that they only added to the people’s burdens, making life under God even harder to bear. They weighed people down without lifting a finger to help the people carry these loads (Matthew 23:4). The Exodus story was about God releasing his people from slavery to live as his royal kingdom, but these Torah teachers turned his kingdom law into a form of slavery. They misrepresented their heavenly sovereign — not as the saviour of his people but as their enslaver.

Jesus planned to do more than lift a finger. Instead of weighing the people down with failure, Jesus planned to take their failures on his own shoulders and bear it for them, as only their king could. Torah mattered, and Jesus planned to fulfil for his people what the heavenly sovereign required:

Matthew 5:17 (ESV)

Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfil them.

Jesus never taught that obedience to the heavenly sovereign was unimportant. Their suffering under Roman rule was indeed because of their disobedience. But what Jesus planned to do was astounding: instead of pointing to their failures and commanding them to do better, Jesus planned to take their disobedience on himself, to face the oppressive powers for them, to be the obedient one who fulfilled Torah for them, to free his people from their oppression.

The crowd on the mountainside could not have known how Jesus would do this, nor how much it would cost him. All they knew was that he had a plan to reinstate God’s reign for them. The king would act on his people’s behalf. Instead of demanding they serve him, he would serve them. That’s good news.

What others are saying

Tom Wright, Matthew for Everyone, Part 1: Chapters 1-15 (London: SPCK, 2004), 41:

Jesus wasn’t intending to abandon the law and the prophets. Israel’s whole story, commands, promises and all, was going to come true in him. But, now that he was here, a way was opening up for Israel—and, through that, all the world—to make God’s covenant a reality in their own selves, changing behaviour not just by teaching but by a change of heart and mind itself.

This was truly revolutionary, and at the same time deeply in tune with the ancient stories and promises of the Bible. And the remarkable thing is that Jesus brought it all into reality in his own person. He was the salt of the earth. He was the light of the world: set up on a hill-top, crucified for all the world to see, becoming a beacon of hope and new life for everybody, drawing people to worship his father, embodying the way of self-giving love which is the deepest fulfilment of the law and the prophets.

R. T. France, The Gospel of Matthew, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007), 183:

We might then paraphrase Jesus’ words here as follows: “Far from wanting to set aside the law and the prophets, it is my role to bring into being that to which they have pointed forward, to carry them on into a new era of fulfillment.”

[previous: Who is the light of the world?]

[next: Do the Ten Commandments apply to Christians?]