Open Psalm 3.

How do you read Psalms? We love the first one: a fruitful tree by the stream. Psalm 2 is more confronting, but we like to read about God’s anointed Son. Then Psalm 3 is about facing enemies. What do you do with that?

If you don’t have enemies, perhaps you skip it and try to find something more joyful? Or perhaps there is someone who’s making your life difficult, so you read on … until you reach verse 7. Are you really supposed to pray, “God smack them in the face and smash their teeth in?”

If you ever end up in court for punching someone, please don’t offer as your defence, “The Bible told me to.”

There is a better way to read the Psalms. They aren’t about “me and God.” You won’t get far if you approach them with the attitude, “What’s in it for me?” You need to ask, “What has this meant for God’s people before me?”

Whose voice?

Who is the me in Psalm 3? No, it’s not you, the twenty-first century reader. Who poured out this graphic lament about the enemies arrayed against him? Any ideas?

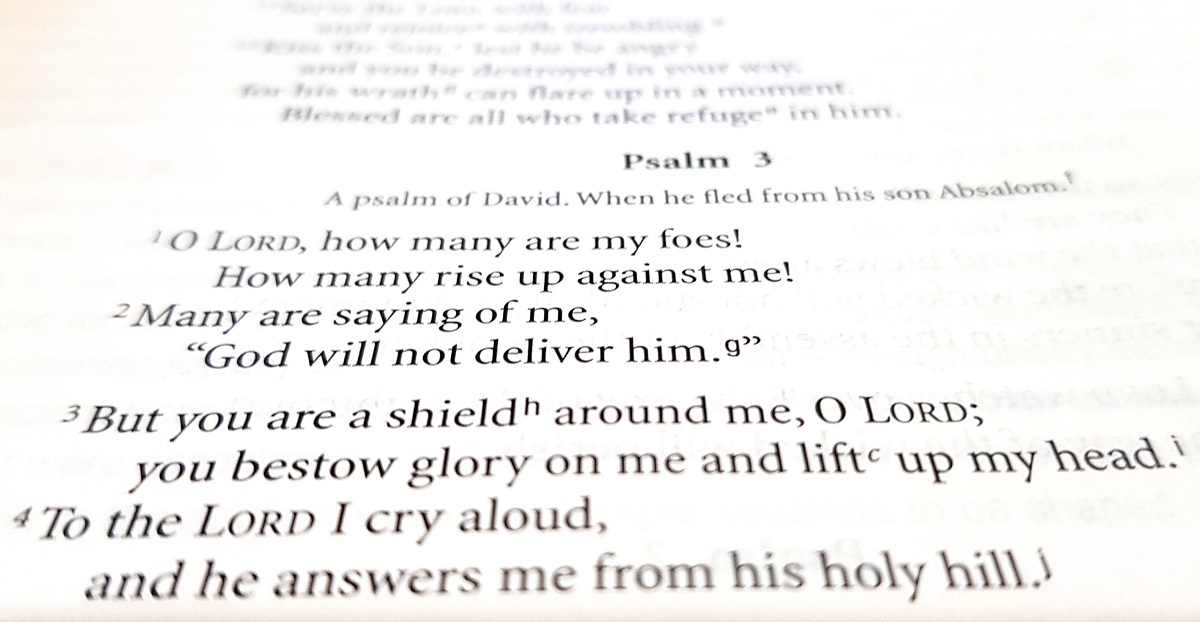

There’s a hint at the top of the Psalm. The compilers who collated the Psalms after the exile provided tips on how to understand and use the Psalm. It’s a Psalm of …?

Yes, it’s David’s voice we’re hearing. The speaker is the king of Israel. When the king speaks of my foes, he’s talking about Israel’s enemies — the armies that threatened the very existence of the salvation project that God was unfolding through Israel. Does that change your approach to the Psalm? Does that change it from “irrelevant to me” to “indispensable to our salvation history?”

King David faced enemies on all sides: Philistines to the south; Syrians to the north; Edomites and Moabites to the east. Tragically, David also faced enemies inside Israel, treachery from his own household. The compilers suggest we picture this Psalm at the time David fled the capital because his own son conducted a coup.

The biggest threat to God’s salvation project was not enemies from other nations. It was the rebellion of God’s own people against the leader he had anointed. This power-grabbing (i.e. sin) within the nation threatened the Davidic dynasty, the survival of God’s nation, and God’s salvation project.

Sense the urgency. Whatever happens to the king happens to the people, so this cry is about much more than God saving David:

Psalm 3 1 O Lord, how many are my foes! Many are rising against me;

2 many are saying of my soul, “There is no salvation for him in God.” (ESV)

The David of each generation

What was David’s significance? He was the Lord’s anointed, the one appointed by God to represent his kingship on earth. That was the significance of each son of David who ruled in generation after generation. It would be a mistake to think that Psalm 3’s meaning became merely historical when David died. The voice of David is the voice of each king, facing Israel’s enemies on behalf of the people in their generation.

Remember what King Hezekiah did when Assyria threatened him? 2 Kings 19:14 says he took the threatening letter, “went up to the temple of the Lord and spread it out before the Lord.” There God answered him, through the prophet Isaiah.

That’s what the Psalm says:

3 3 But you, O Lord, are a shield about me, my glory, and the lifter of my head.

4 I cried aloud to the Lord, and he answered me from his holy hill.

For Hezekiah and the other sons of David, God’s “holy hill” is Zion, the place where God resided in the temple. In David’s day, there was no temple. The Psalm only makes sense when we recognize the voice we’re hearing is not just the original King David but the king of each generation, the sons of David who continued battling the forces arrayed against God’s salvation project through each generation. The voice of “David” in the Psalms is the voice of God’s anointed in each generation.

When David was crushed by enemies

Then came a tragic moment in the salvation story when it all fell apart. Babylon invaded Jerusalem. Their enemies destroyed God’s throne (the ark in the temple) and terminated the Davidic kingship that represented God’s reign. Zedekiah (the last king) watched helplessly as the enemy killed his sons — a graphic portayal that the Davidic kingship had ceased (2 Kings 25:7).

In later Psalms (e.g. 89), you can hear Israel searching for meaning in the face of this tragedy. But even though the compilers knew of the kingship was over, they still included Psalm 3. They gave it pride of place as the first Davidic Psalm. They thought God’s people should still pray the way kings like David and Hezekiah had done:

3 7 Arise, O Lord! Save me, O my God!

For you strike all my enemies on the cheek; you break the teeth of the wicked.

8 Salvation belongs to the Lord; your blessing be on your people!

Despite the loss of the entire country to their enemies, despite the death of the Davidic kingship, Israel continued to pray that the Lord would crush their enemies and save his people.

Their prayers were answered.

When God’s anointed was restored

The Lord’s salvation project started with Abraham. It found its zenith in King David. It had not been destroyed when Babylon invaded. 570 years later, a son of David was born in David’ town and given the name the Lord saves (Jesus), because in him the Lord would save his people from their sins, i.e. from their treachery against God (Matthew 1:21).

I hope you can see why the Psalms apply to Jesus. When we hear David in the Psalms, it’s applicable to the David of each generation, the anointed ruler who represented God’s rule in each generation of Israel’s story. They would have applied to each king in each generation if the kingship had continued, so of course they apply to the Son of David who restored the kingdom of God to the earth. Jesus is the David of his generation (compare Ezekiel 34:23-24; 37:24-25).

Defeating their enemies

He is the Davidic king who restores the kingdom of God, but Jesus uses a radically different strategy to defeat the enemies of God’s salvation project.

When the previous Davidic kings went out to battle, they asked God to strike a blow on their enemies, to defang the armies that planned to chew Israel up and spit it out. But the son of David who restored the kingdom did not follow the traditional strategy. He called his subjects to love their enemies.

That’s because Jesus envisioned a much greater victory than any of his predecessors. Instead of expecting God to destroy their enemies, he expected God to bring them under his kingship, to give him authority over the nations (Matthew 28:18; Luke 24:44).

To achieve this, Jesus faced their enemies. The King of the Jews was condemned by their enemies as a threat to Caesar. But the problem he faced was not primarily Rome: it was the treachery of his own people: those who ruled on God’s holy hill called for the crucifixion of God’s anointed. One of his trusted followers betrayed him, so he was taken outside Jerusalem and hanged on a cross. Like the sons of David before him, Jesus faced the sins of the world and died for the treachery of his people.

But unlike his predecessors, this son of David did not ask for retributive justice, for God to break the teeth of his enemies. He asked for restorative justice, for God to restore them, despite the way they had treated God’s anointed: “Father, forgive them; they don’t understand what they’re doing” (Luke 23:24).

That’s how God’s deliverance arrived for downtrodden Israel. God restored Israel by giving them back his anointed ruler.

Saving the nations

Astoundingly that’s how God brought the nations back under his reign as well. Instead of crushing the nations, God included them under the authority of the resurrected Messiah — a complete redefinition of who constitutes the people of God.

In Christ, the final verse of Psalm 3 becomes a hope far greater than anyone imagined. Salvation has come for the whole earth in the Lord’s anointed ruler. Those who were previously enemies were not crushed but shown benevolence. The blessing for your people extends to the nations who are now under his authority. What an astounding way to resolve the problem of the enemies!

The first verse of Psalm 3 lamented that there was no salvation for the Davidic king, for it seemed certain he would die. The last verse celebrates the success of God’s salvation project in a way that’s so grand it was beyond the imagination of the previous sons of David.

Application

So, what does the Psalm mean for us today? Because Jesus refused to destroy his enemies to become king, we still face enemies of God’s salvation project. This lament is so relevant: sometimes God’s people despair, wondering if Jesus’ method can work, if his approach can save the world from all that’s wrong.

But the resurrection of Jesus has established the reality of what will be through God’s anointed. Salvation has come from the Lord for the earth. In his anointed, the blessing of God’s reign will come to all people. Our hope in him will not be disappointed.

So, we can lament the struggle while God’s enemies try to terminate his salvation project. The most painful enemies are the Absalom or the Judas, those among ourselves who undermine God’s project. But we will not be destroyed by them. God will save. He will restore the earth as the community under his anointed, the kingdom of God through Jesus Christ our Lord.

So, we trust God, and follow his anointed by praying for (not against) our enemies, convinced that salvation belongs to the Lord and his blessing shall be on his people.

Very helpful, thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person